Have you ever experienced a sudden sensation that the world is spinning around you, even when you’re standing still? This disorienting feeling, known as vertigo, affects millions worldwide and can stem from various causes rooted in the inner ear and brain. In neuro-otology, the study of neurological disorders affecting the ear and balance, vertigo stands as a core concept demanding thorough exploration. This article delves deeply into the key elements of vertigo, following a structured mind map that outlines anatomy, physiology, diagnostics, and management. We’ll explore each topic from multiple angles, including historical context, clinical implications, edge cases, and real-world examples, while incorporating visuals, tables, and video links for enhanced understanding. Whether you’re a healthcare professional, a patient seeking answers, or simply curious about balance disorders, this guide aims to provide clarity and depth.

Anatomy of the Inner Ear

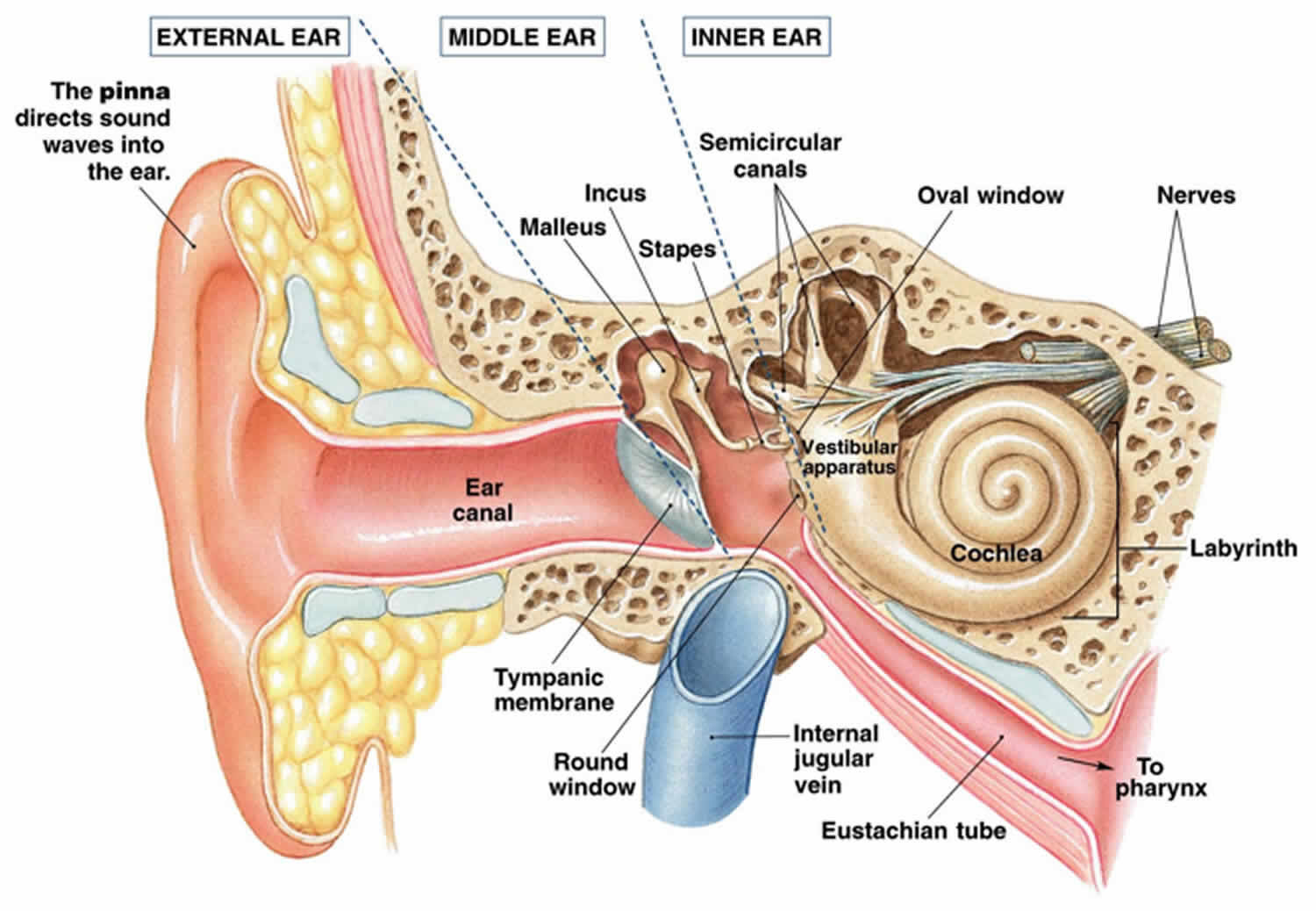

The inner ear, a marvel of biological engineering, is central to both hearing and balance. Nestled within the temporal bone, it comprises the bony labyrinth—a series of fluid-filled cavities—and the membranous labyrinth inside it. The bony labyrinth includes the cochlea (for hearing), the vestibule, and three semicircular canals. These structures are filled with perilymph, a fluid similar to cerebrospinal fluid, which cushions and transmits mechanical signals.

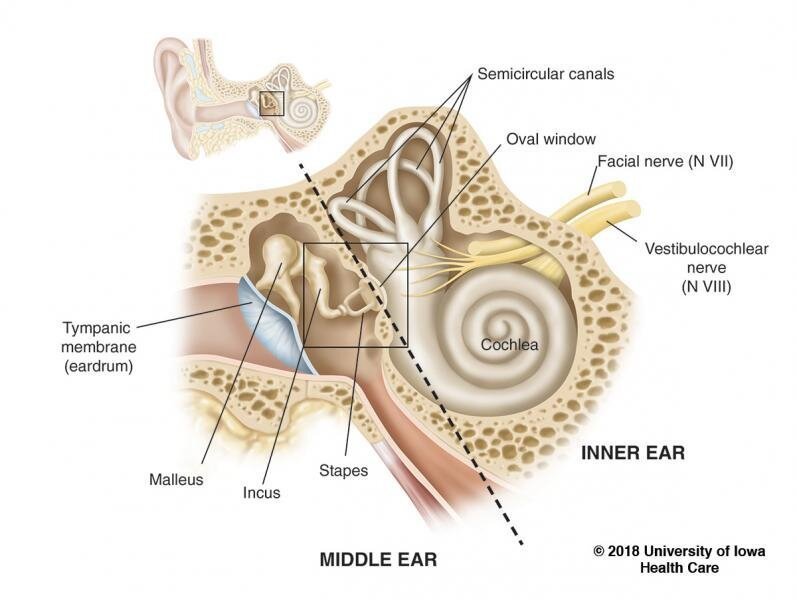

From an evolutionary perspective, the inner ear’s design allows humans to detect motion and maintain equilibrium, a trait honed over millions of years. The vestibule houses the utricle and saccule (otolith organs), which sense linear acceleration and gravity. The semicircular canals, oriented in three perpendicular planes (horizontal, anterior, and posterior), detect rotational movements. Each canal has an ampulla at one end, containing the crista ampullaris—a sensory structure with hair cells embedded in a gelatinous cupula.

Hair cells are pivotal: they convert mechanical stimuli into electrical signals via stereocilia (microvilli-like projections) that bend in response to fluid movement. In vertigo disorders like benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), dislodged otoconia (calcium carbonate crystals from the utricle) enter the canals, causing erroneous signals and spinning sensations.

Clinically, understanding this anatomy is crucial for diagnosing issues. For instance, infections or trauma can inflame the labyrinth (labyrinthitis), leading to vertigo and hearing loss. Edge cases include congenital malformations, such as enlarged vestibular aqueduct syndrome, which predisposes individuals to progressive hearing loss and balance problems from minor head trauma.

To visualize, here’s a detailed diagram of the inner ear anatomy:

Another illustration highlights the semicircular canals and their role in balance:

Implications extend to daily life: pilots and athletes rely on intact inner ear function for spatial orientation. Disruptions can lead to motion sickness or falls in the elderly, emphasizing preventive strategies like balance training.

Blood Supply

The inner ear’s intricate functions depend on a robust blood supply, primarily from the labyrinthine artery, a branch of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) or occasionally the basilar artery. This artery divides into cochlear and vestibular branches, ensuring oxygen and nutrients reach the hair cells and nerves.

Key arteries include:

- Labyrinthine Artery: Main supplier to the membranous labyrinth.

- AICA: Often the parent vessel, also feeding the cerebellum.

- Basilar Artery: Formed by vertebral arteries, it’s a critical trunk for posterior circulation.

- Vertebral Arteries: Paired vessels ascending through the cervical vertebrae, merging into the basilar.

Vascular issues can precipitate vertigo. For example, atherosclerosis or vasospasm reduces flow, causing ischemic damage to hair cells, which are highly oxygen-dependent. In subclavian steal syndrome, blood is “stolen” from the vertebral artery to supply the arm, leading to vertebrobasilar insufficiency and vertigo during arm use.

Rotational vertebral artery syndrome (Bow Hunter’s syndrome) occurs when head rotation compresses the vertebral artery, typically at C1-C2, causing transient vertigo, nystagmus, or syncope. This is more common in individuals with cervical spondylosis or anatomical variants like a dominant vertebral artery.

Here’s a table summarizing the arteries and their roles:

| Artery | Origin/Source | Primary Supply Area | Clinical Relevance in Vertigo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labyrinthine Artery | AICA or Basilar Artery | Membranous labyrinth (cochlea, vestibule) | Ischemia leads to sudden vertigo, tinnitus |

| AICA | Basilar Artery | Inner ear, cerebellum | Infarction causes vertigo, ataxia, hearing loss |

| Basilar Artery | Vertebral Arteries | Brainstem, cerebellum, inner ear | Occlusion mimics vertigo with neurological deficits |

| Vertebral Arteries | Subclavian Arteries | Basilar artery formation | Compression in rotational syndrome causes positional vertigo |

Illustration of the blood supply:

Nuances include variations in vascular anatomy; about 10-20% of people have an asymmetrical vertebral artery, increasing risk for steal syndromes. Therapeutic implications: Antiplatelet therapy or stenting for stenosis, but surgery for compressive lesions.

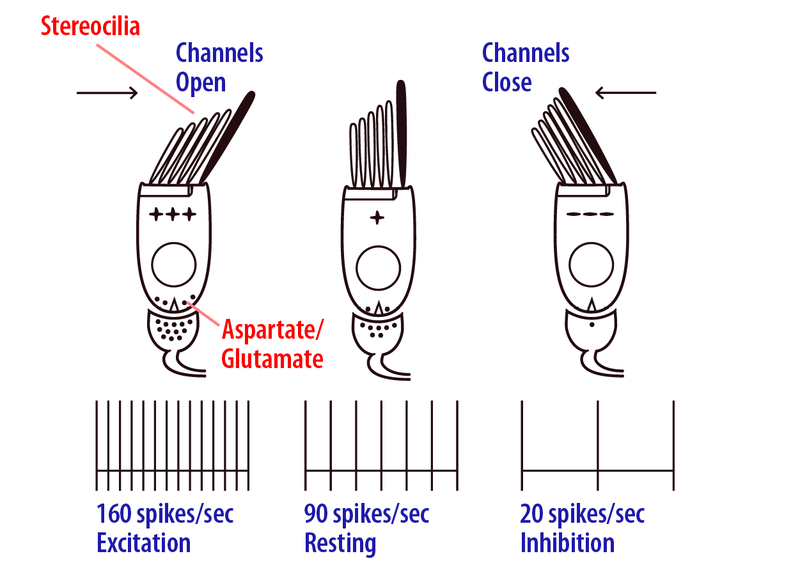

Physiology of Hair Cells

Hair cells in the inner ear are mechanoreceptors translating physical motion into neural signals. In the vestibule, type I and II hair cells in the maculae (utricle/saccule) detect linear acceleration via otoconia shifting the otolithic membrane, bending stereocilia. Potassium influx depolarizes the cell, releasing glutamate to afferent nerves.

In semicircular canals, hair cells in the crista ampullaris respond to angular acceleration. Endolymph flow bends the cupula, deflecting stereocilia toward (excitatory) or away from (inhibitory) the kinocilium. This push-pull mechanism, per Ewald’s laws, ensures precise motion detection.

Ewald’s laws:

- Nystagmus axis parallels the stimulated canal.

- Ampullopetal (toward ampulla) flow in horizontal canal is excitatory; ampullofugal in vertical canals.

- Excitation produces stronger response than inhibition.

Physiologically, resting discharge rates (90 spikes/sec) allow bidirectional signaling: excitation up to 160 spikes/sec, inhibition down to 20.

In vertigo, dysfunctional hair cells— from aging, ototoxicity (e.g., aminoglycosides), or Meniere’s disease (endolymphatic hydrops)—disrupt this. Meniere’s causes fluctuating vertigo due to pressure on hair cells.

Microscopic view of hair cells:

Implications: Hair cells don’t regenerate in humans, leading to permanent deficits. Research into stem cell therapy offers hope, but current management focuses on compensation via vestibular rehabilitation.

Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex (VOR) Arc

The VOR stabilizes gaze during head movement, preventing blurred vision. It’s a three-neuron arc: vestibular hair cells detect motion, signal via cranial nerve VIII to vestibular nuclei, then to oculomotor nuclei (III, IV, VI) for compensatory eye movements.

Components:

- Abducens Nucleus: Gaze center, coordinates horizontal eye movements.

- Oculomotor Nucleus: Controls vertical/torsional movements.

- Medial Longitudinal Fasciculus (MLF): Interconnects nuclei for conjugate gaze.

Mechanism: Head rotation excites one canal’s hair cells (excitation) while inhibiting the opposite, creating compensatory eye movement. Fibers cross midline for push-pull dynamics.

In vertigo, VOR dysfunction (e.g., vestibular neuritis) causes nystagmus and oscillopsia. Edge cases: Bilateral loss (e.g., gentamicin toxicity) leads to chronic imbalance.

Table of VOR components:

| Component | Function | Clinical Note |

|---|---|---|

| Abducens Nucleus | Horizontal gaze coordination | Lesion causes internuclear ophthalmoplegia |

| Oculomotor Nucleus | Vertical/torsional eye control | Damage leads to diplopia |

| MLF | Fiber crossing for conjugate movement | Disruption in multiple sclerosis |

BPPV Diagnostics & Nystagmus

BPPV, the most common vertigo cause, involves otoconia in semicircular canals triggering positional vertigo.

Positional Tests:

- Dix-Hallpike Test: For posterior canal. Patient sits, head turned 45°, laid back with head hanging. Positive: Up-beating torsional nystagmus after latency. Video demonstration: Dix-Hallpike Test Tutorial

- Supine Roll Test: For horizontal canal. Head rolled side-to-side in supine. Geotropic (toward earth) nystagmus indicates canalithiasis.

Nystagmus Types:

- Geotropic: Excitatory, stronger on affected side.

- Apogeotropic: Inhibitory, stronger on unaffected.

- Up-beating Torsional (Posterior Canal): Common in BPPV.

- Down-beating Torsional (Anterior Canal): Rarer.

Ewald’s Laws explain nystagmus direction and intensity.

Clinical Syndromes:

- Subclavian Steal Syndrome: Arm exercise diverts vertebral blood, causing vertigo.

- Rotational Vertebral Artery Syndrome: Head turn compresses artery, vertigo.

Illustration of Dix-Hallpike procedure:

Nystagmus illustrations:

Edge cases: Central mimics (e.g., stroke) show non-fatigable nystagmus.

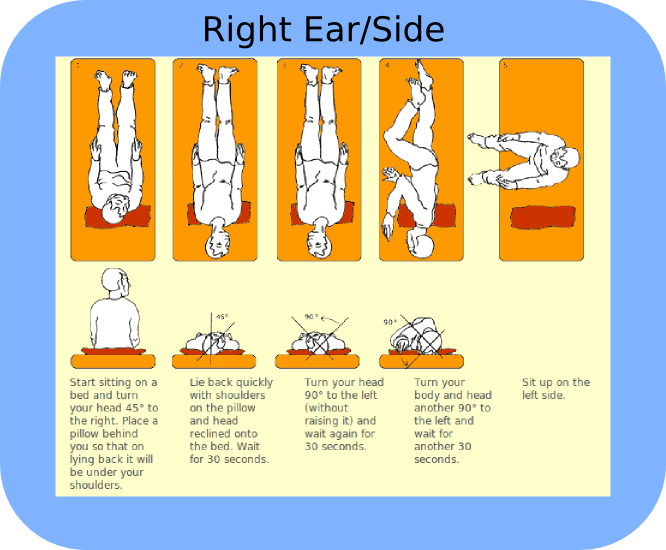

Management & Maneuvers

BPPV management focuses on repositioning otoconia.

- Epley Maneuver: For posterior canal. Series of head positions to guide particles back to utricle. Video: Epley Maneuver Demo

Diagram of Epley steps:

- Gufoni Maneuver: For horizontal canal, geotropic variant. Side-lying then head turn.

- Yacovino Maneuver: For anterior canal, head-hanging to side-lying.

- Brandt-Daroff Exercises: Home habituation, repeated side-lying to desensitize.

Success rates: Epley resolves 80-90% in one session. Recurrence common (30%), so education key.

Table of maneuvers:

| Maneuver | Targeted Canal | Steps Overview | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epley | Posterior | Head turns, supine, roll | 80-90% |

| Gufoni | Horizontal (geotropic) | Side-lying, upward head turn | 70-85% |

| Yacovino | Anterior | Head-hanging, chin tuck, sit up | 75-90% |

| Brandt-Daroff | General habituation | Repeated side-lying | 50-70% long-term |

For persistent cases, consider surgery (canal plugging) or medications (vestibular suppressants like meclizine, short-term).

Conclusion

Vertigo in neuro-otology encompasses a spectrum from benign to life-threatening, with core concepts rooted in inner ear anatomy, physiology, and diagnostics. By understanding these, we can mitigate impacts on quality of life. Always consult professionals for personalized care. Future research may unlock regeneration of hair cells, revolutionizing treatment.